Early History

A Novelty? Microscopes and their Origins

The microscope is synonymous with scientific discovery. From a modern laboratory to a high school science classroom, a microscope is at the center of scientific study at every level. The microscope, however, has not always been considered a reliable scientific tool. The instrument experienced a transformation throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to become an integral instrument in the study of modern science.

Historians have debated the question of who invented the microscope for years without consensus. Several theories indicate that Dutch spectacle-makers Hans and Zacharias Janssen crafted the first microscope in 1590.

However, the term “microscope” did not appear until 1624 when Giovanni Faber, a member of the first Accademia Dei Lincei, an Italian science academy, wrote it in a letter. Galileo Galilei was a member, and many believe he was the first scientist to use a microscope.

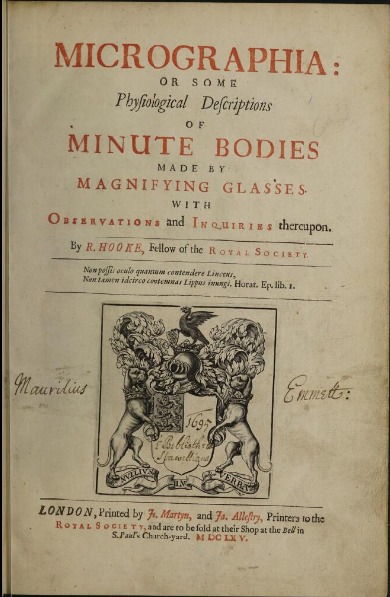

The discovery and subsequent development of the microscope helped launch the Royal Society in England in 1660, establishing it as a serious scientific organization. The Royal Society also advocated for the development of microbiology, a field of inquiry made possible by the microscope. As one of its first publications, the Society published Robert Hooke’s groundbreaking book, Micrographia, in 1665.

The Royal Society and Early Developments

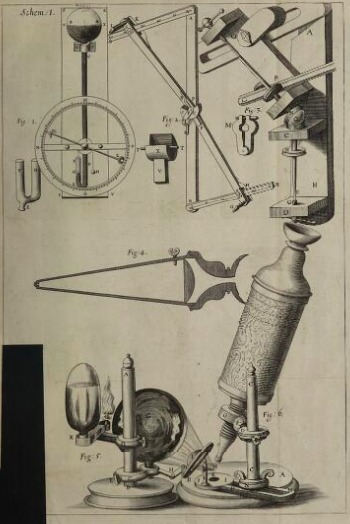

Robert Hooke's publication identified many starting points for the eventual development of the microscope. In his investigation of the structures of plants, Hooke coined the term "cell." The popularity of Micrographia led to the instrument he used in his observations to be known as the "Hooke microscope." His work exposed a miniature world previously inaccessible as he detailed the intricate structures of insects through detailed copperplate engravings. His work brought new understanding to organic structures and inspired many to expand this new field of study.

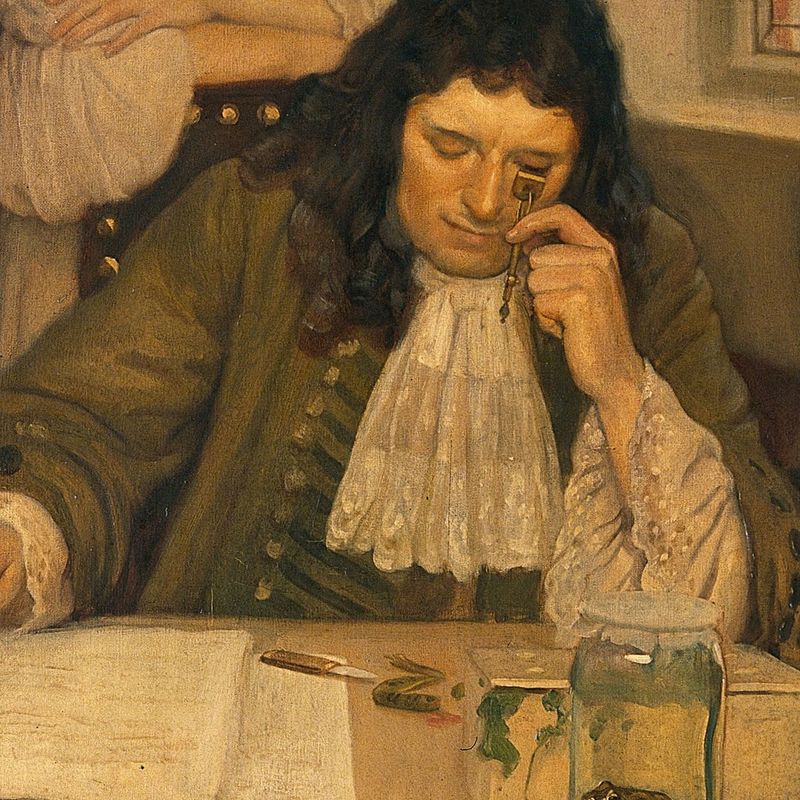

Although the early life of the microscope is muddied, an important figure in its history is Dutch scientist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, who is considered alongside Hooke as the "Fathers of Microbiology." Inspired by Micrographia, Leeuwenhoek's alterations to the design converted the microscope into an instrument of scientific value. He designed a new simple microscope and innovated new methods of grinding lenses to offer clearer observations. The simplicity and power of Leeuwenhoek's microscope demonstrated the opportunities for advancement in the microscope’s design.

Philosophers throughout Europe continued to create microscopes to aid them in scientific inquiry; however, they soon lost interest by the eighteenth century. There were no further developments to the microscope for another century, as philosophers and scientists turned their attention to studying the universe.

The Simple Microscope

The simple microscope design — inspired by Hooke and Leeuwenhoek — made the instrument easy to use and a favorite of amateur botanists and naturalists in the field. Some models included a small pin attachment opposite to the lens so that a specimen (such as an insect or plant) could be held for observation. The "Simple Microscope Replica" does not include this attachment, but future designs incorporated this feature as shown in the "Simple Field Microscope." This design remained popular well into the nineteenth century and became colloquially known as the "naturalist's magnifier" or "flea glass."

Simple Microscope Replica

c. 1800s

This instrument is a replica of the Antonie van Leeuwenhoek simple microscope and is entirely handmade from polished brass. The biconvex glass lens was hand-ground and polished using similar techniques to those used by Leeuwenhoek himself. It has approximately 100 x magnification. The replica is treated with "Renaissance" micro-crystalline wax.

Simple Field Microscope

c. 1800-1850

This Georgian miniature brass field microscope has a turned ivory handle, specimen pin, and a pair of lenses that screws into the top. The lens arm and handle are hinged to the slotted bar so that the instrument can be folded and fitted into a small papier-mâché case. Popular during the nineteenth century, this microscope is similar to a model produced by W & S Jones, a successful British optician, and manufacturer of scientific instruments.

Stanhope Lenses

Invented by Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope, the Stanhope lens is a moderately powerful lens used primarily to inspect specimens and read small prints. These small instruments were also used to view microphotographs.

In 1839, John Benjamin Dancer developed a process to shrink images to a microscopic level but regarded this work as a “hobby” and did not pursue to market his new invention. French photographer and inventor René Dagron, however, saw the potential to develop microphotographs and market them to a wider audience. He adjusted the Stanhope lens into a simple microfilm viewer and placed the lens and microphotographs into everyday items, such as jewelry and pens. These devices became known as “Stanhopes” and were popular souvenirs during the late nineteenth century.

Waistcoat Pocket Stanhope Microscope

c. 1800-1850

The handle of the waistcoat magnifier is made from either bone or ivory and the lens is surrounded by metal. The lens is moderately powerful and was used to inspect specimens and read small prints or images. The instrument measures just 4.9 cm and was used mainly as a novelty item.

Stanhope Pocket Microscope

c. 1800-1850

The pocket Stanhope microscope is set in a bone frame and has a moderately powerful lens. This item was used mainly as a novelty item to inspect specimens or read small prints. These instruments were usually very small, with this magnifier measuring only 4.5 cm tall.

The Coddington Lens

In 1812, William Hyde Wollaston invented an improved version of earlier magnifiers by crafting a model consisting of a spherical glass by mounting two hemispheres of glass together with a small stop between them. Sir David Brewster further developed the lens which then caught the attention of Henry Coddington, a British natural philosopher. In 1829, Coddington further refined the Wollaston-Brewster lens by modifying the shape of the groove, after which the lens became known as the "Coddington lens," although Coddington never claimed the invention.

The Coddington lens became popular among botanists, naturalists, and amateurs due to its small size, simple design, and portability. The handheld magnifier consists of a single lens with two curved sides, and a groove cut around the middle of the glass, allowing it to offer a clear image from 1 inch away.

Wilson Screw Barrel Microscope

Made from brass and ivory, this instrument can be dismantled and placed into its velvet-lined case. The instrument can be focused by twisting the screw-like thread which changes the distance between the lenses. This is one of its defining features and why it is referred to as a "screw barrel" microscope. The instrument comes with a range of accessories that include ivory slides, a selection of lenses, and small forceps. James Wilson improved the design originally created by Dutch mathematician Nicolaas Hartsoeker in 1694. In 1702, Wilson published a description of his plan in the Philosophical Transactions, the Royal Society's journal.

Desktop Magnifiers

The desktop magnifier is made from silver and has four decoratively etched legs. These magnifiers were used during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to assist people with bad eyesight in reading. They would slide the magnifier across the page to read the small text. This magnifier stands at just 3 inches tall.

A Resurgence

The nineteenth century saw industrial expansion throughout Europe. The creation of railways, the growth of cities, and shifts in the social and economic map of Europe paved the way for further scientific discovery. Microscopes were slowly accepted as tools of scientific study; however, they still faced limitations due to issues with their lenses. Lens makers still struggled with achieving flawless products, and the established method they used did not guarantee clear and perfect observations.

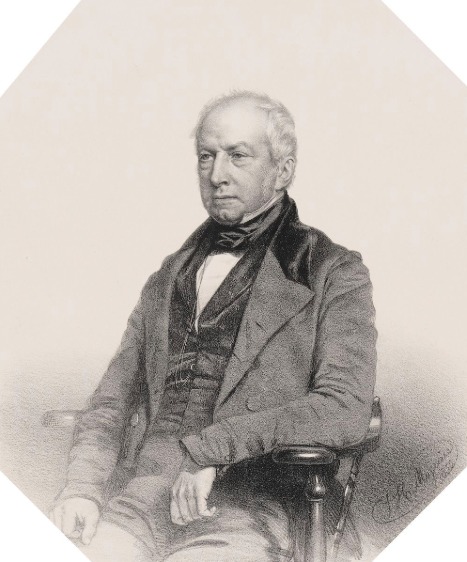

Enter Joseph Jackson Lister. In 1824, the British optician and wine merchant began his work to correct this issue. In 1830, Lister published an article entitled "On Some Properties in Achromatic Object-Glasses Applicable to the Improvement of the Microscope," outlining his discovery that the correction of lens combinations and the distances between them minimized blurring and imperfections. This reignited the scientific community’s interest in the microscope as a serious tool of research and drove scholars to improve its design further.

During the nineteenth century, scientific expeditions offered new opportunities for advancements in the natural sciences, as well as an environment for the microscope to thrive. While on a voyage to Australia, Robert Brown, a Scottish botanist, and paleobotanist, identified how the structure of pollen grains could help identify the classification of plants. In his publication, he coined the term "cell nucleus." Scientists have since questioned his ability to view the intricate cell structures with the microscope he used. Luckily, his microscope still exists, and further experiments have proven the microscope’s power and confirmed his findings.

Handheld Microscopes

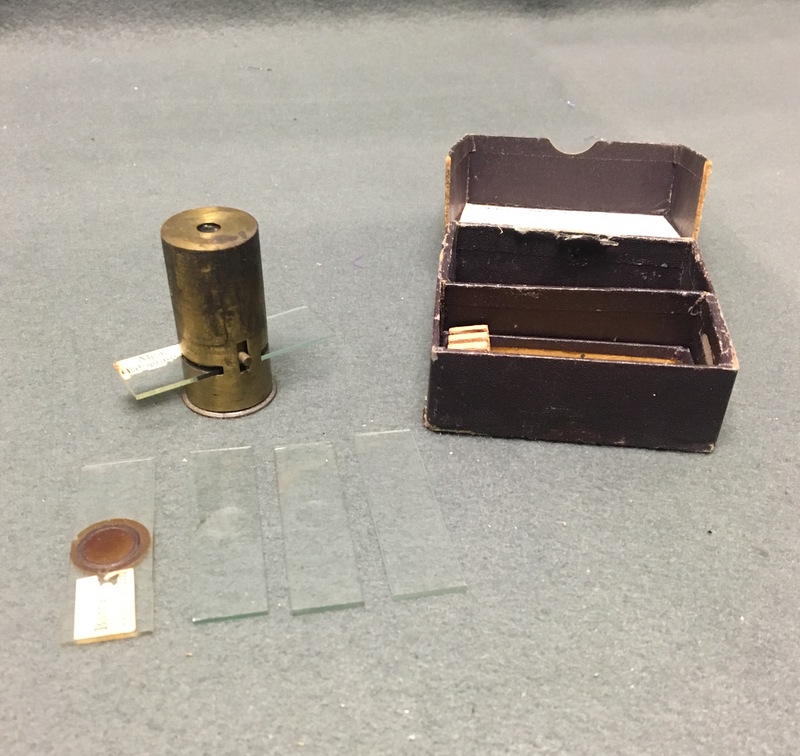

Many microscope manufacturers created simple, handheld instruments that became popular among amateurs due to their affordability. This design was also known as the “universal” model and rose in popularity during the twentieth century. The simple design includes a single lens in a cylinder frame with a cut-out section for a prepared slide. This style of microscope was widely manufactured in France and Germany due to its low-cost, durability, and simplistic design. These features meant it was a favored scientific tool amongst hobbyists.

Pocket Handheld Microscope

c. 1900

Standing at only 1 ¾” tall, this simple microscope could be transported in an individual’s pocket, hence its name. Many considered this scientific instrument versatile as it allowed observation of specimens too small for a magnifying glass while in the field. Unlike the more complex and bulkier microscopes, the “universal pocket microscope” was very portable with good magnification as it could magnify up to 50 times linearly. This model comes with its original cardboard box with both prepared and new glass slides as well as clear instructions printed on the interior of the lid.

Cary-Gould Microscope

The Cary-Gould microscope’s defining feature is its fitted case that also acts as the base of the instrument. British scientific instrument makers William Cary and Charles Gould popularized the style as they developed and manufactured portable microscopes during the nineteenth century. Initially designed by Cary, Gould also developed case-mounted microscopes and produced them under his name. Due to their development of this model, Cary and Gould’s became forever linked to design.

The microscope had a simple design that meant it could be easily dismantled to fit into its case and transported into the field. The style was a favorite amongst hobbyists during the nineteenth century as it came with an array of accessories, including powerful lenses. It was also the preferred model for botanists and naturalists as it could be used as both a single and a compound microscope.

"Cary-Gould type" Pocket Microscope

c. 1800-1825

This microscope is an example of the “Cary-Gould style” microscope. It comes with an array of original accessories that includes three prepared bone slides, two bullseye condensers, a live box, and two dissecting instruments. Rather than attaching to the lid, this microscope fastens to the interior of the case and has a hinge joint that allows the instrument to be angled.

Cary-Gould Pocket Microscope

c. 1830-1850

Signed by “Cary of London,” this microscope is another example of the “Cary-Gould” style that many manufacturers produced. The microscope’s pillar fastens into the brass section that also functions as the lock for the case. The case has velvet-lined compartments that secure its accessories in place.

William Cary (1759-1825) was a British scientific instrument maker who invented the Cary-style microscope. Charles Gould (1786 - 1849) was also a British scientific instrument maker and served as an apprentice to Cary during his early adulthood. Gould continued to develop Cary's design and produced his own instruments. They popularized the style of microscope which resulted in the design being permanently linked with their names, even today.