The Female Scientist and Literature

Women in Science

Male Victorian scientists vehemently rejected the enrollment of women in universities. Scientific societies banned women from attending meetings and discouraged them from studying the "unladylike" subject of science altogether. Men generally ridiculed the idea that women were capable of serious scientific work but in some circumstances accepted their participation in areas such as botany and geology. Affluent women from influential families, however, had the opportunity to develop connections within the scientific community, and in doing so kept up to date with philosophical and scientific development, albeit from a distance.

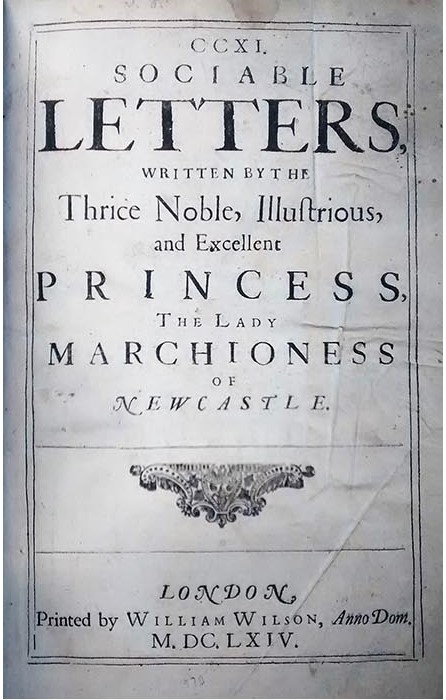

The first woman to attend a meeting at the Royal Society was Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle, in 1667. Her male counterparts furiously protested her presence. Cavendish, a natural philosopher, and prolific writer became a controversial figure due to her avid interest in natural sciences. Although she was considered an intelligent woman, her male counterparts trivialized her contributions to the subject. This sexist attitude continued in the scientific community well into the twentieth century, highlighted by the fact that the next admission of a woman to the Royal Society occurred in 1945, over 250 years later.

Did you know...that Margaret Cavendish, a pioneer for women in the sciences during the eighteenth century, was not a fan of the microscope! She critiqued Hooke's microscope, stating it was "deluding Glasses" rather than "true informers."

In her writings, Cavendish comments on a wide range of topics important to seventeenth-century British society. She explores issues such as war, peace, science, medicine and career options for women. In this book, Cavendish offers her insights through the format of her letters. While she was known for her work in the emerging field of scientific study, she also wrote and published poetry, plays, and fiction under her name, which was unusual as many contemporary female writers published anonymously.

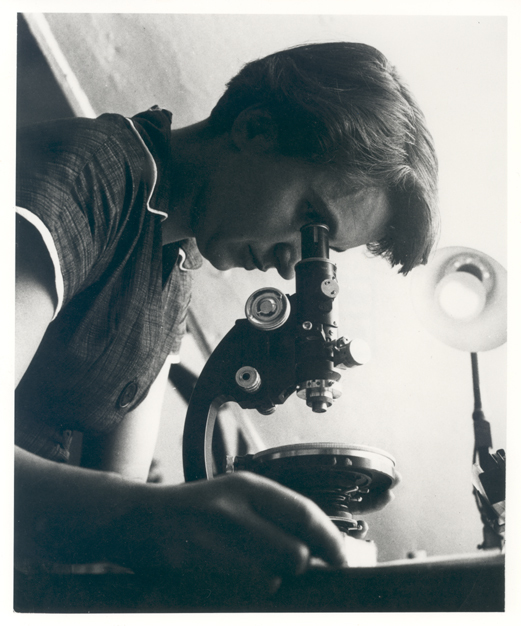

Women continued to study science despite intense adversity. The accessibility of the microscope during the nineteenth century offered women the opportunity to engage in research in their own homes. Initially connected with elite male scientists, nineteenth-century microscopes made their way into the homes of the middle and upper classes as a result of the growth of manufacturing in Britain. The microscope became a symbol of intellect and thus secured its place in the homes of those who could afford it.

Women at the Microscope

Rachel Carson

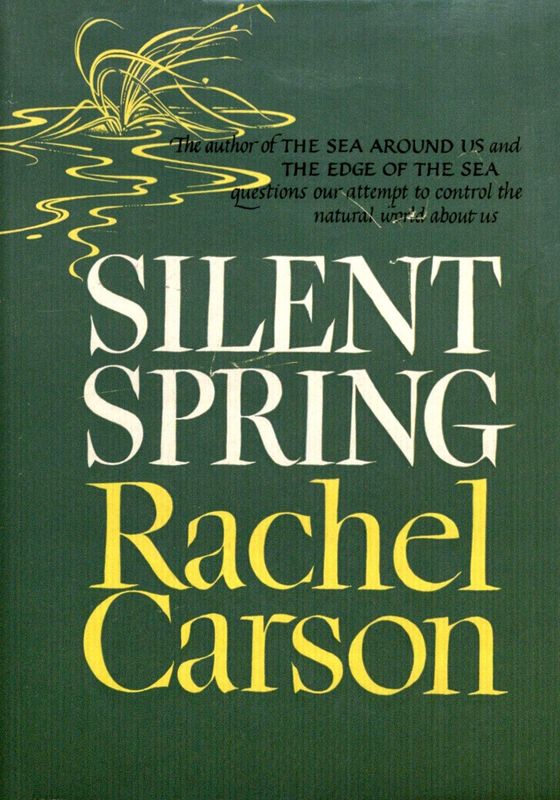

In her book, Carson argues that the increased use of pesticides has caused adverse environmental effects. She directs the blame at the chemical industry as she stated they intentionally spread misinformation about their products. She also accused public officials of accepting the industry’s claims without further investigation or oversight.

Rachel Louise Carson was born on May 27th, 1907 in Springdale, Pennsylvania. While studying at Pennsylvania College for Women (later Chatham College), Carson switched her major from English to Biology after being inspired by her biology professor. She went on to obtain a master’s degree in marine zoology from Johns Hopkins University. She went on to become a well-known ecologist, author and conservationist. Many of her writings, including Silent Spring, are credited with furthering the growing global environmental movement during the 1950s and 1960s.

Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Franklin was born in Notting Hill, London on July 25th, 1920. Franklin studied physics and chemistry at Newham College, Cambridge, where she obtained a second-class honor in her final exams in 1941. The University of Cambridge did not offer women titular degrees until 1947 and offered those who had achieved the requirements before the date the title retroactively.

Franklin pursued a successful career as a chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work became central to the understanding of the structures of DNA, viruses, coal, and graphite. She died at the early age of 37 after losing her battle to ovarian cancer, and the scientific community had recognized her academic contributions during her lifetime. However, her vital role in the discovery of the double helix was not widely known until the 1970s, years after Francis Crick, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for the discovery in 1962.

Magic Glasses and Literature

Women had to carve a place for their scientific contributions through the publication of "popular science." Maria Edgeworth and Arabella Buckley, for example, placed themselves into the role of educators through their publications. Their social status and gender allowed them to forge successful literary careers with little resistance from the scientific community. Edgeworth and Buckley stayed within the confines of the "appropriate" position for nineteenth-century women by adopting the role of educator, directing their literature at children.

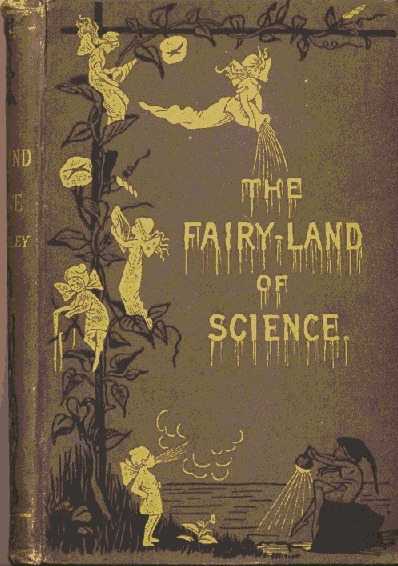

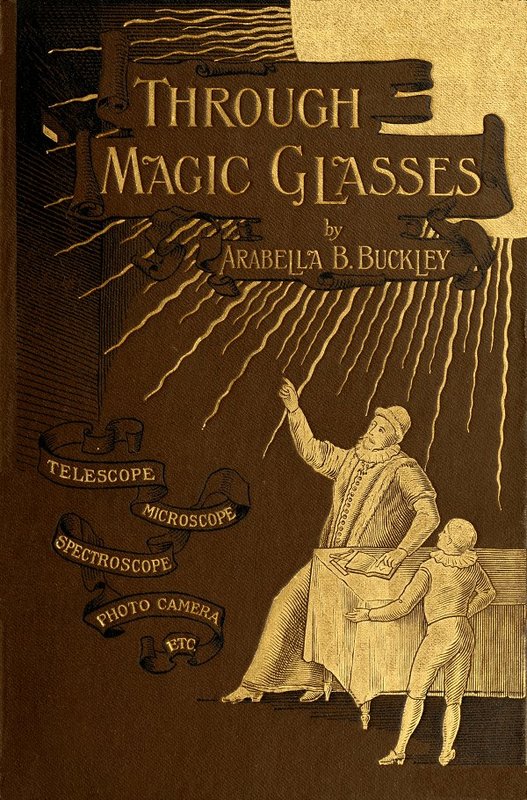

Born into a wealthy family, Arabella Buckley worked as an assistant to Charles Lyell, a prominent Scottish geologist, until his death in 1875. She published many books, including Through Magic Glasses and Other Lectures (1890), which aimed to educate children in an array of scientific topics. She presented the material simply with a maternal voice, instructing children about the study of science and how to correctly use a microscope. Maria Edgeworth argued that our books of science were full of unintelligible jargon, which made them inaccessible to the public. In response, she wrote scientific novels that the public could comprehend. Women like Maria Edgeworth and Arabella Buckley brought a sense of wonderment to science, while scientists worked towards removing any semblance of imagination from scientific rhetoric.

In an age of scientific enlightenment, public interest in fantasy literature grew. The microscope opened up a new miniature world to the popular imagination, a place where, before the microscope, small creatures lived unobserved. Fairy-science literature emerged as a sub-genre of children's literature and represented an unlikely partnership of natural science writing and fantasy. Books such as Fairy Frisket: or, Peeps at Insect Life (1874) and, Fairy Know-a-bit; or a Nutshell of Knowledge (1866) became tools for parents and teachers to educate their children. The Victorian fairy reflected the adult's encouragement for children to look closer into the natural world.

Botanical "School" Microscope

C. 1870-1880

This botanical “school” microscope has a similarly simple design to the Cary-Gould models that allowed it to be dismantled easily to fit into its case. The case also had a dual function as the base of the microscope when in use. As seen in this example, botanical microscopes came with an array of parts and accessories that included a body tube, stage, substage mirror, dissecting tools, and a selection of objective lenses. The instrument got the name “school microscope” as it was utilized for educational purposes due to its simple design, portability, and inexpensive cost. This design resembled the earlier eighteenth century model of the “Ellis Aquatic” microscope produced by John Cuff, a prominent instrument maker in Britain. Cuff created a simplified aquatic microscope for John Ellis, a naturalist, who required the instrument for his studies. Ellis’ name became permanently attached to the design, despite Cuff designing the model.

This botanical field microscope is an example of a very popular design during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Due to its small size and simple design, the instrument could be easily used in the field for amateur microscopists. This style is similar to a Cary-Gould style microscope as the case functions as a base for the instrument. Depending on the manufacturer, the microscope would have slightly different attachments and designs to the original style. Like many pocket-style microscopes, the instrument can be dismantled to fit into a case. The microscope comes with an array of accessories that include three slides, three objective lenses, forceps and two live boxes that were used to hold specimens or samples of water.

Did you know… that Charles Darwin used a botanical/aquatic microscope on the famous Beagle Voyage to observe specimens of barnacles and plants.

Female Science Writers

During the nineteenth century, many botany books were focused on women. Titles such as John Lindley’s Ladies’ Botany (1834-37) and Botany for Ladies by Jane Loudon (1842) were published and aimed to offer instructions for women to participate in botany. Botany was considered an acceptable form of scientific study for women due to the alliance of herbal healing and gardening to femininity. However, this was not accepted by everyone as some men believed that botany was inappropriate for women due to the sexual nature of botanical terminology.

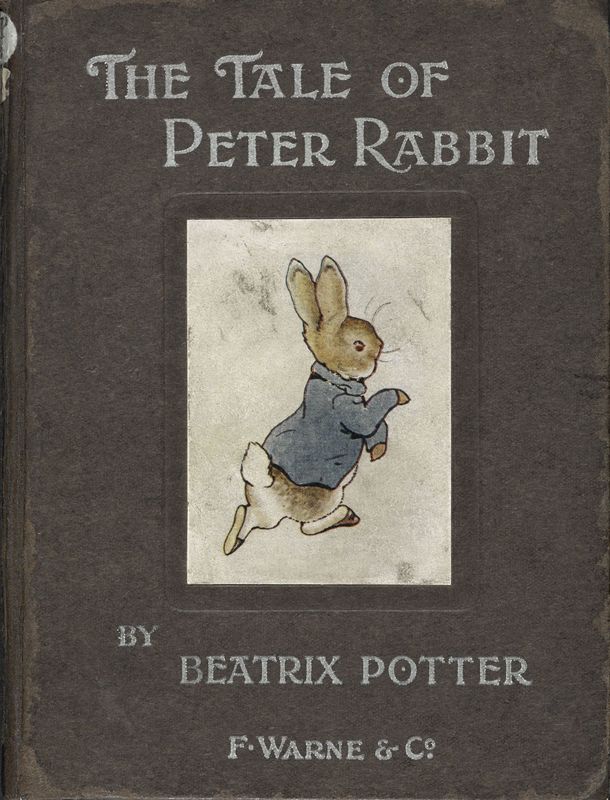

Did you know… that before she created Peter Rabbit, Beatrix Potter was fascinated by mushrooms! Mycology is the study of fungi, which Potter studied with interest, sketching microscopic drawings of fungus spores. She wrote a paper entitled, “On the Germination of the Spores of the Agaricineae” with her observations and submitted it to the Linnaean Society in 1897. However, due to her gender and status as an amateur, she was not able to attend the meeting to introduce her study and subsequently withdrew it.

Beatrix Potter

As well as being a well-known children’s writer and illustrator who created characters such as Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddle-Duck and Tom Kitten, Beatrix Potter was also an avid botanist and entomologist. During her childhood and early adulthood, Potter made many visits to the Natural History Museum in London, England, which was located less than a mile from her home. She would take time to study and sketch the insect collection, and at home, she taught herself how to prepare specimens in slides so she could view them through her brother’s microscope. Later in life, Potter became an avid conservationist who supported the work of the National Trust in preserving the countryside in Britain. She also restored and maintained farms that she bought or managed and became keenly interested in sheep farming.

Arabella Buckley

A sequel to The Fairy-Land of Science (1879), Buckley used a narrative of fairy tales and mythical beings to educate children on how to view science with imagination. For example, she explains how fairy rings (a naturally occurring ring or arc of mushrooms) through the narrator of a magician teaching a young student. Through this narrator, she outlines how to use different scientific instruments — such as a microscope — to investigate the earth. She described the science of a simple water drop and the various ways her audience could investigate for themselves using an array of scientific methods, including a microscope.

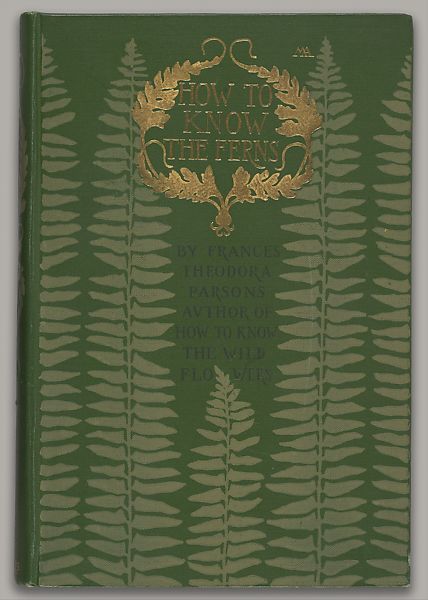

Frances Theodora Parsons

Frances Theodora Parsons was born in New York in 1861. She developed a love of botany in her childhood during the summers she visited her grandparents in rural New York state. After the death of her first husband, William Starr Dana in 1890, Parsons spent her mourning period taking long walks in nature and rekindling her interest in nature. From these walks, she wrote How to Know the Wild Flowers (1893), a guide to American wildflowers, which garnered praise from Theodore Roosevelt. She went on to write more books on botany, writing some for children. Her third book, Plants and Their Children (1896), is listed as one of the 50 best children's books of its day. In 1899, she published How to Know the Ferns as a companion to her first guidebook.