Scientific Discovery

The microscope made many of the scientific discoveries possible that have shaped our modern world. It has provided insight into a range of scientific studies such as medicine, forensic science, and genetics. Below are examples of discoveries that would have been impossible without the microscope:

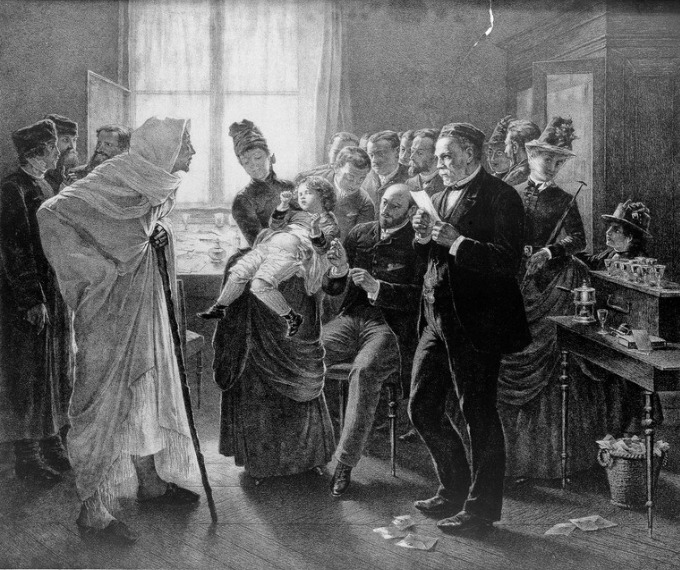

Germ Theory (1861)

Germ theory changed the practice of medicine radically, as it brought a new understanding of diseases. Germ theory states that many diseases are caused by the presence of microorganisms in the body. Pioneered by Louis Pasteur, a French microbiologist, germ theory garnered support throughout Europe and is still used today. Using his microscope, Pasteur identified that microorganisms cause fermentation and disease. This discovery resulted in the creation of the process called pasteurization, which assisted the saving the wine and beer industry. Germ theory also assisted Pasteur in creating vaccines for diseases such as rabies, anthrax, smallpox, and puerperal fever.

Genes and Inheritance (1866)

Gregor Mendel, a Czech scientist, pioneered the theory of genes and the process of inheritance. He developed his groundbreaking theory by examining pea plants and tracked the inheritance patterns by breeding them. He discovered that they followed basic statistical rules, wherein some traits were dominant while others were recessive. He published his findings, but they remained unnoticed for decades. In 1900, three scientists discovered his paper. Erich Tschermak, Hugo de Vries, and Carl Correns verified his findings, and so the study of genetics began.

Malaria (1897)

Sir Ronald Ross, a British medical doctor, received the Nobel Prize for Physiology of Medicine in 1902 for his work on the transmission of malaria. In 1897, Ross published his findings on the presence of malarial parasites in the gut of Anopheles mosquitos, confirming that the disease was transmitted by this particular species. His discovery laid the foundation for how to combat the disease.

By the twentieth century, manufacturers developed new models of microscopes to meet the growing needs of the scientific community. The “dissecting microscope” was developed to allow individuals to dissect specimens under the microscope. Although not an invention of the twentieth century – the earliest reference to this style can be dated back to 1862 – the design underwent many modifications during the early twentieth century.

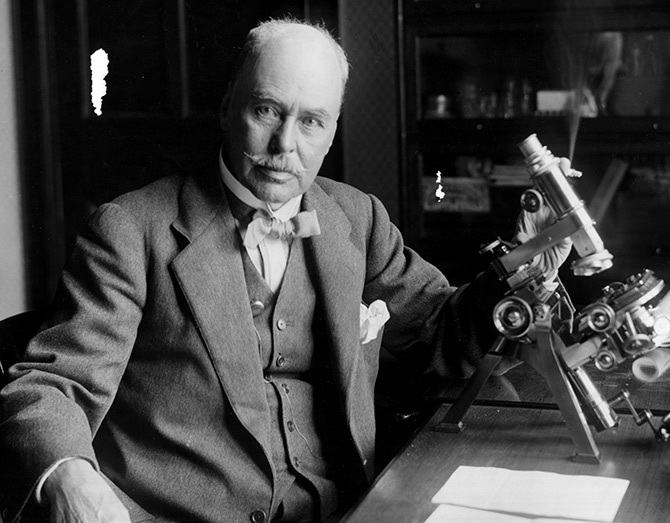

Ernst Leitz Dissecting Microscope

c. 1900-1925

The design included a large, reinforced glass stage that could withstand the pressure of dissection. This style also included objective lenses that could be slotted easily into place (rather than screwed) as not to disturb the specimen. These features assisted Ross in his studies on malaria, as he owned an Ernst Weisz dissecting microscope during his scientific career. While this instrument functioned as a simple microscope, other models also included a body tube attachment that allowed it to be used as a compound microscope.

Ernst Leitz’s origins can be tracked to the Optical Institute, founded in 1849 by Karl Kellner in Wetzlar, Germany. In its early years, the Optical Institute mainly manufactured telescopes; however, by the mid-nineteenth century, microscopes became their main product. After Kellner’s untimely death at 29 years old from tuberculosis, his partner Friedrich Christian Belthle took over the company and operated under the name, Optical Institute Kellner and Belthle. In 1865, Ernst Leitz joined the company as an engineer and by 1869, took over the company after the death of Belthle. He renamed it the Optical Institute of Ernst Leitz, and by 1892, Leitz had opened up a sales office in New York City. After Leitz died in 1920, his son Ernst Leitz II took over as sole owner of the business.

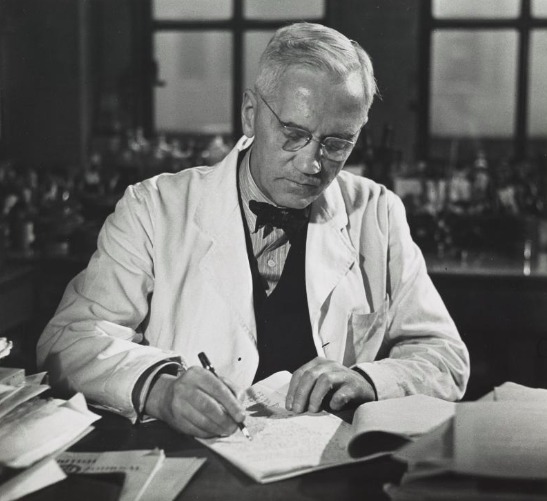

Penicillin (1928)

In 1928, Scottish physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming returned from vacation to what he initially thought was a spoiled experiment. A Staphylococcus (Staph) culture plate had shown mold; however, with closer inspection, he realized that no bacteria grew near the mold. On further investigation, Fleming found that all the bacteria had died when exposed to the mold. He refined the substance and named it “penicillin.” The discovery became instrumental in fighting infection in soldiers during the Second World War. Fleming received the Nobel Prize for his contributions to physiology and medicine in 1945.