The Development of the Microscope

Crafting the Microscope

From its conception in the late sixteenth century, the microscope has been an area of fascination for many individuals. Seventeenth-century European opticians also operated as scientific instrument makers as they crafted their own instruments, many taking the form of a microscope. This collection holds many examples of scientific instruments from prominent makers that span three centuries or manufacturing history.

Edmund Culpeper

Edmund Culpeper (1670-1738) was an English scientific instrument maker who began his career as an engraver. He went on to craft simple microscopes before he developed significant improvements in the tripod-mounted compound microscopes. His name has become synonymous with the design as these developments brought him fame in the scientific community. He is well known for manufacturing the “screw barrel microscope” – for example, see 180421 in this collection – invented by James Wilson.

Culpeper pioneered this tripod-mounted compound microscope with a fixed circular stage. This microscope cannot be angled like other styles, and so a rotatable substage mirror is needed to observe a specimen. The brass and mahogany instrument comes with a custom pyramid-shape case so the microscope can fit securely inside. This microscope comes with an array of accessories that include six lenses, glass slides, and a spring-loaded stage attachment.

Nachet et Fils

Camille Sebastien Nachet began his career as a lens maker under Charles Chevalier, a well-known microscope maker in the early nineteenth century. By 1839, Nachet founded his own microscope manufacturing company in Paris, France, and by the mid-nineteenth century became one of the leading French producers of microscopes. He participated in the Great London Exhibition in 1851 and won a gold medal for his work. Nachet’s became well-known for being the first to construct the “inverted microscope” from designs created by the American chemist, Dr. J. Lawrence Smith. Although not invented by Nachet, the model became known as the “Nachet’s chemical microscope” as they were the first to manufacture the microscope. The new design made it possible to successfully examine hot fluids as previous attempts using microscopes failed due to the vapor rising and obscuring the lens.

Nachet et Fils Microscope

Circa 1800

The microscope is signed "NACHET ET FILS 17 Rue St Severin Paris" and made from brass and cast iron. The instrument has a distinctive H-shaped base that is weighted so the microscope is supported when angled for observation. The French biologist, Louis Pasteur, used a microscope similar to this instrument in his scientific investigations into the process of pasteurization.

Below is the cover of Real Heroes, published by Parents' Magazine Press in 1942. It shows an illustration of Louis Pasteur using his microscope to fight the "unseen enemy." This comic book was published over 40 years after his death and highlights the importance his discovery had in science and medicine.

Sentry-Box Microscope

The art of manufacturing microscopes also appealed to craftsmen outside the scientific community. Around the 1750s, artisans in Nuremberg (Bavaria) Germany — famous for creating wooden toys — produced microscopes made from softwood and pasteboard. Craftsmen mimicked the popular styles of brass microscopes in their wooden creations, and four styles prevailed from the region: Culpeper-type, sentry box-type, solar, and side pillar-type. This practice continued for over a century in the area as the wooden microscopes became a popular souvenir. Due to their widespread popularity, identifying a specific manufacturer is challenging.

Sentry-Box Type Microscope

c. 1775-1825

In this instrument, the lower compartment holds the substage mirror with a cut out for the slides to be secured. The pasteboard body tube is partitioned into three sections which are separated by turned ornamental rings. The bottom section is covered in shagreen paper, the middle section in plain paper, and the top section in a decorated painted paper. The microscope has three lenses — the eye, field, and objective lenses. The bottom of the instrument is signed "JFF" within a heart, one of a few signatures often appearing on these microscopes.

Booming Industry

"The microscope is now firmly established as a household instrument, and an invaluable assistant in aid of the education and mental refinement of the rising generation." J.S. Bowerbank at the Royal Microscopical Society, 11 May 1870.

The Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) in Britain ignited the rise of the middle classes as new markets emerged in response to new methods of manufacturing. This created more investment opportunities for those outside the landed gentry and church to make money. Within this boom, the microscope became an object of great interest for opticians due to their focus on the human eye and expanding its potential. Soon, scientists and manufacturers saw the microscope as an extension of the eye.

Manufacturers began to modify the instrument to fit the needs of the professionalizing scientific class. However, the broader public also began to take an interest in the microscope and the insights it could bring. Manufacturers widened their customer base by adapting the microscope to be more affordable and simpler to use. The growth of scientific societies throughout Britain and America helped integrate the microscope as a household object for the middle and upper classes. Organizations such as the Royal Microscopical Society (1839) and Quekett Microscopical Club (1865) were dedicated to the development of the microscope and its accessibility to the public. They published instructional manuals for the instrument which offered the public guidance in developing their own skills and interest in the microscope.

Microscope Accessories

As well as the selling microscopes, many manufacturers produced and sold microscope accessories such as artificial light sources. These products allowed individuals to use microscopes without relying upon the sun as a light source for observations

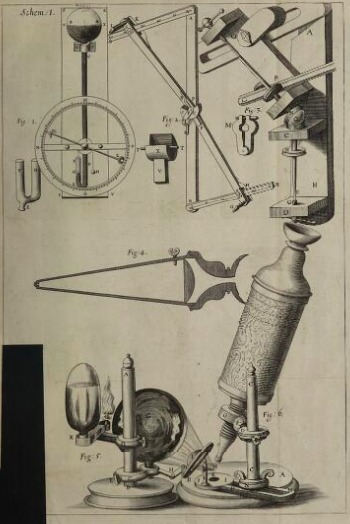

An early example of this is the use of a candlestick with a condenser attachment. The condenser was used to focus the light from the flame to the substage mirror of the microscope. These were used before the invention of gas lamps by microscopists so they could continue their work after sundown. The origins of this device can be traced back to Robert Hooke’s book, Micrographia, in which he included a sketch of his microscope with the assistance of a candlestick.

Later in the nineteenth century, developments on artificial light sources meant that microscopists could now use gaslighting to aid their observations. This example of a gas microscope lamp has an adjustable magnifier that can be rotated to focus the light onto the specimen. These instruments were popular in the nineteenth century and used a flammable substance such as paraffin or alcohol to fuel the flame.

Charles Collins

Charles Collins (1837-1915) was born to Henry Collins, a noted publisher of maps and globes. Charles worked at the Royal Polytechnic Institute, London, before opening up his own business. The Institute was a school of science, engineering, languages as well as an entertainment center that featured lectures, microscope exhibits and dramatic performances. After leaving, Charles became an optician and continued to create microscopes as well as microscope accessories. He became a prominent manufacturer of microscopes, going on to join the Quekett Microscopical Club in 1865 and the Royal Microscopical Society in 1866.

Microscope Manufacturing

During the mid-nineteenth century, optical instrument makers further developed the design and functionality of microscopes. In 1830, Joseph J. Lister, a renowned microscopy pioneer, published a paper to the Royal Society entitled "On Some Properties in Achromatic Object-Glasses Applicable to the Improvement of the Microscope." Lister perfected the achromatic lens by correcting the spherical and chromatic aberrations that caused distortions during observations. Lister collaborated with Andrew Ross and James Smith — pre-eminent manufacturers of microscopes — on his work with achromatic lenses, and both utilized this development in their future instruments. A notable result of this improvement was the advancement of histology, the study of the microscopic structure of tissue into an independent science.

These advancements in microscope lenses meant that scientists could rely on microscopes for serious biological research as well as medical diagnosis. As histology grew as a discipline, it was introduced into the medical school curriculum, and professorships of histology were appointed. Microscope manufacturers needed to meet the demand for inexpensive microscopes for students and so manufacturing grew. This collection holds examples of these manufacturers' instruments designed for a growing scientific community.

Andrew Ross

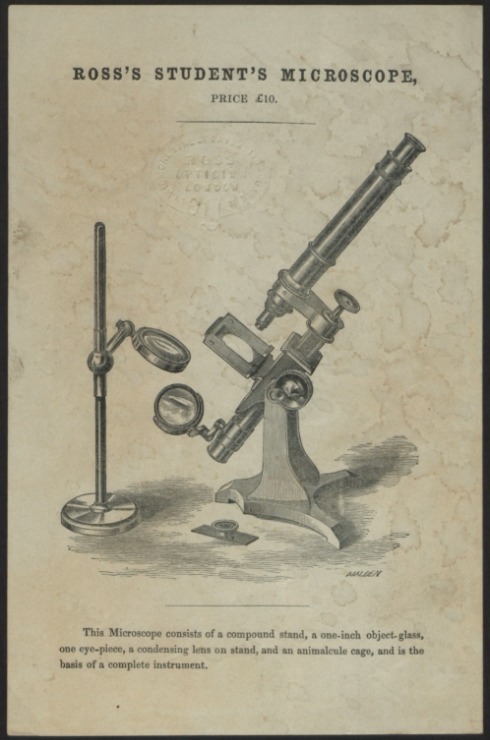

Andrew Ross Microscope

c. 1841-1847

This compound microscope followed a similar design to many microscopes being manufactured during the nineteenth century. It has a splayed Y-shaped foot as well as a mechanical stage with additional attachments which include a bullseye condenser and specimen pin. The microscope comes with an array of accessories that include a stand-alone bullseye condenser, and a selection of objective lenses.

Andrew Ross established Andrew Ross & Co. in 1830. He garnered a reputation throughout his career for producing high-quality microscopes. He was awarded the Gold Isis Medial twice, first for his improvement on astronomical and mathematical instruments, and secondly, for his improvements on the achromatic lens. Ross instruments were displayed at the 1851 Great Exhibition, winning first place for his microscope design. The company used the Ross name until 1975 when Avimo absorbed it.

James Smith

James Smith was a mathematical instrument maker in London during the early nineteenth century. Joseph Jackson (J.J) Lister approached Smith to produce microscopes to accommodate the achromatic objectives he had designed. Lister instructed Smith in the intricacies of grinding lenses, and Smith began retailing microscopes under his own name by 1839. The Royal Microscopy Society became one of Smith’s early clients, and they received their first microscope around 1841. In the early 1840s, Richard Beck — nephew of J.J Lister — apprenticed with Smith, and in 1847 they formed the company Smith & Beck together. Smith left the company in 1866, and the company’s name changed to R & J Beck. During the First World War, they produced a range of optical products such as microscopes, trench periscopes, eye test glasses, and other equipment.

Smith, Beck & Beck Student Microscope

Circa 1871

This microscope represents the emergence of binocular microscopes during the nineteenth century as manufacturers worked to produce a functional binocular tube design. This style signifies what many of us would recognize as a modern microscope. Ernst Leitz II, the son of German mechanic and mathematician Ernest Leitz, created the physical beam splitter that allowed for the design to be functional. Nineteenth century manufacturers configured and developed a functioning binocular microscope, and it became the norm for those designing and producing microscopes after.

Negretti & Zambra

In 1850, Henry Negretti and Joseph Warren Zambra founded their company after immigrating to Britain from Italy. They produced scientific and optical instruments while also operating a photographic studio in London. Manufacturing under the name Negretti and Zambra, they became very successful throughout Europe and America. They participated in the 1851 Great Exhibition and received an award for their products. Negretti & Zambra became the official opticians, and optical instrument makers to Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, the Royal Observatory, and the British Admiralty. Expanding their expertise to producing photographic equipment, they took the first aerial images of London from a balloon. The company prospered into the twentieth century and participated in the production of instruments for the Ministry of Munitions during both World Wars.

Negretti & Zambra Compound Microscope

Circa 1870

This compound microscope has a decorative Y-shape foot and comes with a glass display case. The instrument comes with an array of accessories that include a stand-alone bullseye condenser, objective lenses in brass canisters, and a cardboard slide. The microscope is mounted on a mahogany platform that allows the microscope to slide smoothly into the case. This model is an excellent example of a late nineteenth century compound microscope as many designs began to incorporate a hinged pillar that allowed the microscope to be angled for more comfortable observation, unlike many of the eighteenth century models.

James Swift

In 1853, the optical instrument maker James Powell founded James Swift & Sons in London, England. J. Swift & Sons became known for their high-quality products, as well as their use of innovations in microscope design, such as their use of the “spiral” rack and pinion coarse focus. Captain Robert Falcon Scott, a Royal Navy officer, and explorer used a Swift microscope on the RRS Discovery for the 1901-1904 expedition into the Antarctic regions. It was the first official British exploration of the Antarctic, and the microscope Scott used was named the “Discovery” model after the expedition. Adam Hilger and E. R. Watts and Son Ltd. took over the company in 1946 as they had close connections with the Swift family, and the company became known as Hilger & Watts Ltd.

J. Swift & Sons Histological Compound Microscope

c. 1897

This microscope’s design included many peculiar features to appeal to military doctors and traveling scientists at the turn of the century. The microscope has four legs, of which the two rear legs are collapsible to allow for the instrument to be packed away efficiently. As the microscope is collapsible and able to fit securely into its case, it was advertised as a “portable microscope” despite its substantial size and weight. This instrument is made from brass, but an aluminum version was available as a lightweight option. Its intricate design and portability appealed to scientists who required a powerful but easily transportable instrument for their work.

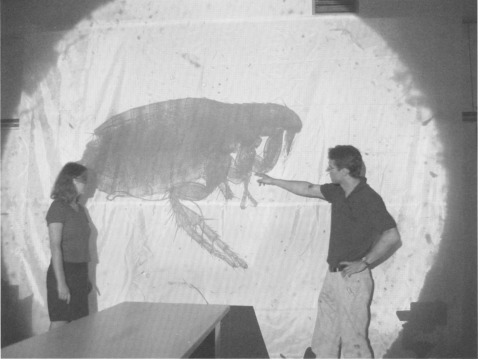

By the late nineteenth century, laboratories also required instruments for projecting images, and manufacturers utilized eighteenth century designs to meet this demand. Manufacturers used the model of “magic lanterns” – a tool developed in the eighteenth century – to project photographic positives on glass plates. The instrument functioned by passing a beam of light through the slide and an enlarging lens to create a projected image. With the development of electric lamps, projection microscopes were used to present an image of histological slides onto a screen. Projection microscopes followed a similar design of the solar microscope, introduced around 1740 by John Cuff. The only difference was the source of illumination, which had advanced from sunlight to lamp.

Dollond Solar Microscope

c. 1760s

The Solar microscope utilized sunlight to produce a projected image of the chosen specimen. Designed to be mounted to a window shutter, artificial light sources — such as candles or gas lamps – could not be used on this model and limited the time this instrument could be used. Similar to many designs of the eighteenth century, this style did not offer precise results required for detailed scientific investigation. Many nineteenth century microscopists critiqued the effectiveness of this design for accurate projection, which led to others building on the model to produce “projection microscopes” that could use artificial light.

The Solar microscope utilized sunlight to produce a projected image of the chosen specimen. Designed to be mounted to a window shutter, artificial light sources, such as candles or gas lamps, could not be used. This limited the time that instrument could be used, as it relied on the illumination of the sun. Similar to many designs of the 18th century, this style did not offer precise results required for detailed scientific investigation. During the nineteenth century, many microscopists critiqued the effectiveness of the design —inspite of no improvements since its development — identifying it as a novelty, and form of entertainment.